Coercivity and Remanence in Permanent Magnets

A good permanent magnet should produce a high magnetic field with a low mass, and should be stable against the influences which would demagnetize it. The desirable properties of such magnets are typically stated in terms of the remanence and coercivity of the magnet materials.

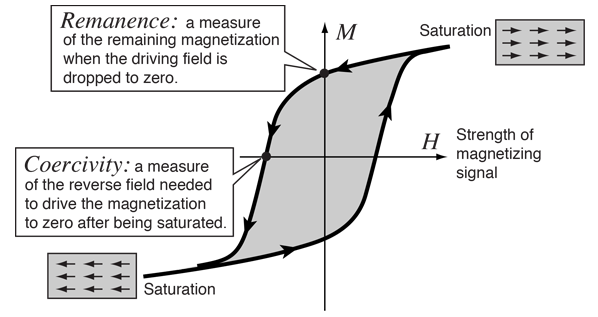

When a ferromagnetic material is magnetized in one direction, it will not relax back to zero magnetization when the imposed magnetizing field is removed. The amount of magnetization it retains at zero driving field is called its remanence. It must be driven back to zero by a field in the opposite direction; the amount of reverse driving field required to demagnetize it is called its coercivity. If an alternating magnetic field is applied to the material, its magnetization will trace out a loop called a hysteresis loop. The lack of retraceability of the magnetization curve is the property called hysteresis and it is related to the existence of magnetic domains in the material. Once the magnetic domains are reoriented, it takes some energy to turn them back again. This property of ferrromagnetic materials is useful as a magnetic "memory". Some compositions of ferromagnetic materials will retain an imposed magnetization indefinitely and are useful as "permanent magnets".

The table below contains some data about materials used as permanent magnets. Both the coercivity and remanence are quoted in Tesla, the basic unit for magnetic field B. The hysteresis loop above is plotted in the form of magnetization M as a function of driving magnetic field strength H. This practice is commonly followed because it shows the external driving influence (H) on the horizontal axis and the response of the material (M) on the vertical axis. Besides coercivity and remanence, a quality factor for permanent magnets is the quantity (BB0/μ0)max. A high value for this quantity implies that the required magnetic flux can be obtained with a smaller volume of the material, making the device lighter and more compact.

| Material | (T) | (T) | (kJ/m3) |

| BaFe12O19 | |||

| Alnico IV | |||

| Alnico V | |||

| Alcomax I | |||

| MnBi | |||

| Ce(CuCo)5 | |||

| SmCo5 | |||

| Sm2Co17 | |||

| Nd2Fe14B |

The alloys from which permanent magnets are made are often very difficult to handle metallurgically. They are mechanically hard and brittle. They may be cast and then ground into shape, or even ground to a powder and formed. From powders, they may be mixed with resin binders and then compressed and heat treated. Maximum anisotropy of the material is desirable, so to that end the materials are often heat treated in the presence of a strong magnetic field.

The materials with high remanence and high coercivity from which permanent magnets are made are sometimes said to be "magnetically hard" to contrast them with the "magnetically soft" materials from which transformer cores and coils for electronics are made.

References

Myers

Ch 11

| HyperPhysics***** Condensed Matter ***** Electricity and Magnetism | R Nave |